Anonymity or Pseudonymity

Anonymity has gotten a really bad rap on the Internet, especially when it comes to abuse. It’s seen as a way for abusers to protect their real identities and act with impunity – and sometimes, this can be the case.

But anonymity and pseudonymity are also really empowering ways for women and other minorities to explore online spaces, voice their opinions and play with various identities.

Or a way to feel comfortable in a large public space.

‘I am just shy, I’m not afraid of anything. It’s not fear that makes me go anonymous. Rather, I’m not the kind of person who would like to be centre-stage or identify with her opinion openly.’

-- Sowmya, interviewed for Don’t Let It Stand

And because of their (relative) freeing potentials, anonymity and

pseudonymity are often employed as direct or indirect strategies to

address abuse.

For women who feel their online voice and identity leaves them or their families vulnerable to hate, who have already faced large amounts of abuse, or who occupy minority positions (in relation to caste, religion, or sexual orientation for example), anonymity and pseudoynmity are ways to both protect and free themselves. While you may sometimes wish that you could have used your legal name, there can be real solace in taking a step back, and pleasure in discovering new, safer, and even more playful ways to exist online.

(fyi: broadly speaking, anonymity is using online platforms without a name or under multiple shifting names or IP addresses, whereas pseudonymity is using a name not linked to your legal identity, but one that tends to remain the same across platforms and is often accessed from the same IP address. In practice, though, most people who use a pseudonym online tend to think of themselves as ‘anonymous’)

For many women who identify as feminists, the relentless barrage of online abuse becomes difficult to take. In the face of increasingly personal attacks — listing home addresses, family members, and other identity markers (known as ‘doxxing’) — some feminists are adopting pseudonyms. Or at least wishing they could.

Guardian columnist Jessica Valenti says in an interview with The Washington Post that if she could start her online experience again (ranging from the articles she writes to the blog she founded, Feministing.com) that she might prefer to do it under an alias.

‘I don’t know that I would do it under my real name… [It’s] not just the physical safety concerns but the emotional ramifications’

-- Jessica Valenti

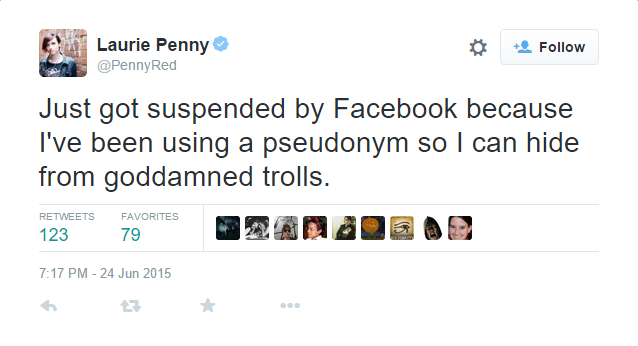

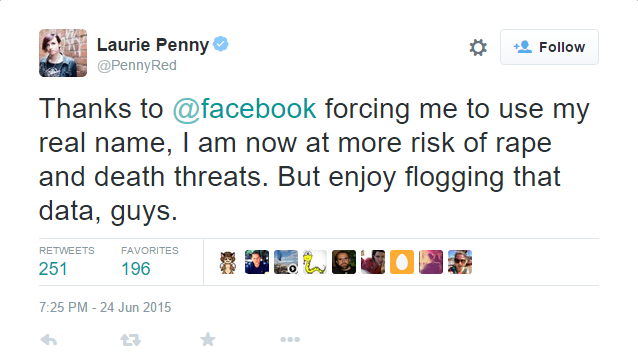

Of course it’s impossible to start over, but some women are making the attempt to start anew. In 2015 British feminist author Laurie Penny adopted a pseudonym on Facebook to avoid being trolled (if you check out her Twitter mentions, you’ll sadly see just how much vitriol she receives). But (no) thanks to Facebook’s ‘real name policy’, Laurie’s pseudonymous account was banned.

Luckily, some women who aren’t as well known as Laurie have managed to slip under Facebook’s totally unhelpful radar, and pseudonymously exist on its platform.

As a result of being stalked, Stroop Wafel quit Facebook altogether. But when she had to be back on it for work (millenials!) she opened an account splitting her first name into the fields for first and last names. Unfortunately, obsessive stalker found her again. This time, she chose to chuck her name altogether and use a pseudonym (nope, Stroop Wafel is not what she goes by on FB).

But this has impacted Stroop’s professional life, as employers these days expect to find a profile of their employees.

Facebook itself does not understand that for a lot of folks anonymity is safety and to force everyone to disclose their name marginalizes those who can't, and it's violent.

-- Stroop Wafel, in an interview with the Internet Democracy Project

Thankfully, not all platforms are as difficult about ‘real’ names as

Facebook. Blogging platforms, Twitter and Instagram will all let you

exist under whatever name you prefer.

Of course it’s a far-from-ideal situation that women who used to speak under their names are retreating into pseudonyms, but for many this has been an important means to carry on using their voices online.

Takeaway

Women facing large amounts of online abuse sometimes choose to use a pseudonym instead. Though this doesn’t solve the broader problem, it can be a temporarily effective — and even freeing — solution.

Not all women’s decisions to be anonymous or pseudonymous online are direct responses to abuse, but these decisions often anticipate potential abuse that may arise as a result of using one’s real name. Harassers often go out of their way to hit you where it hurts, and one big concern for many women is threats directed towards their families.

‘Right now, one peril of the system is that… there is very less possibility of keeping things in a safe lock. So whether it’s my child’s name... my husband’s office. Everything is known, even if I have not given it. So people would come and tell me, “I know where your kid studies in school so beware” ...They know mothers will be particularly sensitive to things like this.’

-- Nidhi, interviewed for Don’t Let It Stand

As a result, women whose blogs or social media accounts include

stories about their families (often relegated to the category of ‘mummy

blogs’) frequently choose to write pseudonymously.

It’s often the case that no matter how hard you try to stay anonymous, someone will eventually connect the dots between your online and offline identities. After all, how many reggae-loving, cat-picture-taking, feminist writers are there in your small town?

‘The more you hold on to anonymity, the more people want to know who you are... It’s only later on that I realised that anonymity is a joke on the Internet and that eventually people will find you.’

-- Trishna, interviewed for Don’t Let It Stand

Yet for many women, it’s still worth trying.

Takeaway

Choosing to be anonymous or pseudonymous online is often a pre-emptive measure used by women to protect themselves and their families, even though there’s always the risk that they will eventually be ‘found out’.

What sometimes starts off as a desire to simply escape the pressures and ties of an offline identity, or to protect that identity, can also lead to something more playful and freeing. Especially for women with marginalised identities. Take sex workers.

Many sex workers with online identities choose to remain pseudonymous because of the massive amounts of stigma that still exists around their profession ('cause you know, sex is for the making of the babies not for the making of the monies, okay). Pseudonymity allows sex-working women who otherwise face discrimination to speak freely, find community, and advocate for rights. But it also has very different freeing potentials.

Sex workers of VAMP, a collective based in Sangli, Maharashtra,

exist on Facebook anonymously, moving across multiple, shifting

profiles.

For sex workers, it’s been freedom and expression. In the virtual world, these multiple identities give you so much access. And I am also talking about caste and class... You can’t be friends with people across caste and class... in [a] small town. But on[line], they are friends.

-- Meena Seshu, Sangram (VAMP’s parent organisation), speaking at a meeting in 2013 held by the Internet Democracy Project

In this way, anonymity frees women not only from the stigma of their profession and monitoring by law enforcement. Changing Facebook accounts and names (luckily unnoticed by Facebook for now) also allows them to playfully explore multiple identities and create new friendships and relationships, in ways that simply would not be possible in the offline world.

A 2013 article found that young men living in a homeless shelter in Delhi were similarly adopting alternative identities online so as to escape the stigma of their offline worlds. Raju Shaikh, for example, alternatively presented himself as an ex-ESPN employee living in New York.

‘I tried making friends as [myself] Raju, but it didn’t work out’.

’So I started the new [account] so I can improve my English and make new friends and one day have someone to visit in the U.S.’

For people who occupy various marginalised positions in society, online anonymity or pseudonymity can temporarily free them from hierarchal constraints. If your identity means that you face casteism, racism, or any other pick from the bag of discrimination, experiencing the Internet under a new persona can be a fun, affirming experience.

Takeaway

For people with marginalised identities, online anonymity can be way to playfully explore various personas and create new relationships that transcend barriers of prejudice.

Speaking of playing with identities, welcome to finstagram. Just like Instagram, but not quite.

Finstagrams are locked, pseudonymous Instagram accounts with an intentionally small number of followers (mostly in the low double digits). Especially popular among teenagers, finstagrams are the place you don’t need to curate your shiny-happy-self all day long. They’re the place for ugly selfies, weird obsessions, mundane photos and screenshots of text messages. In other words, finstagram — the amalgamation of fake + Instagram — is actually a place for reality.

Since the accounts are locked, the only way someone can follow you is if you accept their follow request. Which means that you completely control who your followers are and who you share information with.

‘Everything that goes on my regular Instagram is a picture of me and other people, and everybody looks good, and it feels important. On finstagram, you post whatever you want because you don’t care’

-- Rebecca Cibbarelli, 18, quoted in the New York Times

For many teenagers and young adults, these pseudonymous accounts are allowing them to explore the one thing that the hyper-visibility of social media doesn’t look kindly upon: what their lives actually look like.

(The information in this example is taken from a New York Times article

titled ‘On Fake Instagram, a Chance to Be Real’ by Valeriya

Safronova]

Takeaway

In a shiny-happy social media culture, pseudonymous accounts can be important ways to express how you really live and feel without the fear of judgment.

Tech companies are also jumping onto the anonymity bandwagon. Apps to communicate anonymously are being developed across the interwebs, fresh for download to your smartphone.

There’s Whisper, an app to ‘express yourself openly and honestly’, marketed under the tagline ‘Ever wondered what the people around you are really thinking?’

Or there’s YikYak, a US location-based social network premised on anonymity and interacting ‘freely’

And of course, Facebook didn’t want to lose out on this trend, so while refusing to drop (or fundamentally change) its real name policy, they introduced Facebook Rooms in 2014: ‘a space for people to talk about their interests without having to be anxious that it could be connected to their real identities’.

All this, of course, on top of the tons of forums online where the majority of users operate pseudonymously, ranging from Reddit to gaming platforms.

But how well do these newer apps protect your identity?

As this Slate article reports, Whisper is totally open about the fact that it tracks its users, and

in fact, is also considering targeted advertising. Since many of

these apps are location-based, they pull data from your phone

including your contact list and GPRS information so as to give you

the gossip that’s most directly relevant to you - anonymously of

course.

And as for Facebook Rooms (which closed its doors in 2015), it might have claimed to be anonymous, but they still needed you to provide an email address. Which for most people, is probably the same one they used to sign up for Facebook, so it doesn’t take much for Facebook to make the connection between someone’s ‘real’ and anonymous identities.

Another issue with many of these apps has been that, rather than focusing on anonymity for reasons of privacy or freedom, they’ve focused on the idea of gossip. Targeting schools and college campuses, these apps have seen multiple instances of bullying and hate. And unlike older, more established platforms, like Reddit, that have moderators and clear guidelines, these apps have insufficient mechanisms in place for dealing with abusive behaviour.

Theoretically speaking, it’s great that tech companies are responding to users’ desire for privacy. Practically speaking, though, it would be great if they’d prioritise a truly anonymous experience that isn’t built on gossip or data mining. Here’s hoping.

Takeaway

There are several apps offering anonymous communication, though it’s important to consider whether they really fulfill your needs.