Community Support and Initiatives

One of the difficult things about getting abused online can be that

your offline communities often don’t understand ‘what the big deal is’.

What’s more, women are sometimes reluctant to share experiences of

online abuse with families or partners, for fear of being blamed (a.k.a.

that dreaded phrase, ‘what were you doing there in the first place?’).

So for many women, support from online communities is invaluable.

I started looking out for people who were of similar thinking [...]. I started reaching out to them. I went out of my way to find like-minded people. It is a sense of support that I feel I wanted […], that if I’d be abused, they will come forth in [the] open and support.

-- Rishika, interviewed for Don’t Let It Stand

They are friends, but they are also online. If need be, they come up on the threads and shut the guy up. Or they offer me some kind of advice on how to bypass this. And if [necessary], they will also be ready to come to the police with me.

-- Kalpana, interviewed for Don’t Let It Stand

Whether it’s sympathetic messages meant only for you, or having others on your side when you decide to confront an aggressor; whether it’s friends who come to your help spontaneously, or more structured community-led initiatives and technologies – knowing that people have got your back can make things a lot easier.

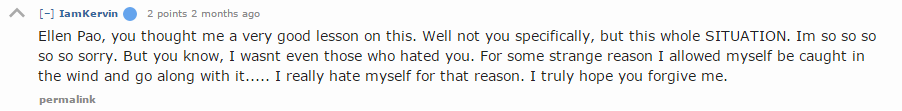

When former Reddit CEO Ellen Pao attempted to strengthen Reddit’s anti-harassment policies, including by banning revenge porn, she was subject to what she calls ‘one of the largest trolling attacks in history’. After numerous threats of violence and an aggressive petition calling for her resignation, Pao stepped down from her post at Reddit amidst exactly the kind of vitriol she sought to remove.

But what stood out for Pao during this time were the messages of support she received. She writes in the Washington Post,

As the trolls on Reddit grew louder and more harassing in recent weeks, another group of users became more vocal. First a few sent positive messages. Then a few more. Soon, I was receiving hundreds of messages a day, and at one point thousands… Many shared their own stories of harassment and thanked us for our stance.

In addition to sending her messages of support, users started engaging with Pao’s abusers directly on Reddit.

Interestingly, as the conversation began to shift, some of her abusers also apologised.

Pao concludes:

In the battle for the Internet, the power of humanity to overcome hate gives me hope. I’m rooting for the humans over the trolls. I know we can win.

Takeaway

Whether the abuse you are facing is a one-off or ongoing, and whether you are dealing with one harasser or an entire mob – having other people come to your aid can be a real source of the relief, strength, and energy you need to stand your ground online.

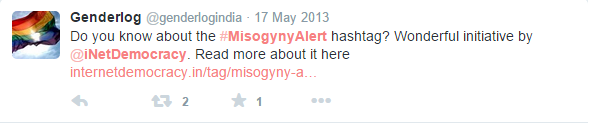

Back in 2013, when we were researching the first phase of Don’t Let It Stand, we met with some women to talk about online abuse. And out of one of these meetings, the Twitter hashtag #MisogynyAlert was born. The idea was that women facing abuse could hashtag a tweet with #MisogynyAlert so that an informal group of us following the hashtag could intervene.

Here’s some enthusiasm from around the time of its launch.

We weren’t the only ones thinking along these lines. Later that year, the Twitter account @fembatsignal – a feminist version of the distress signal device first conjured up in the Batman comics – emerged as a way for women to alert feminists and allies to abuse.

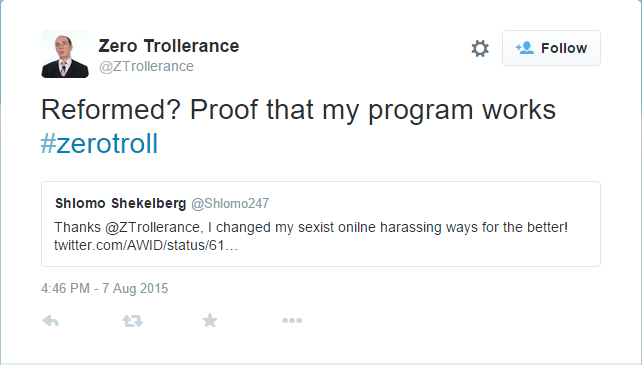

And in 2015, Zero Trollerance launched a super fun self-help guide for trolls (more on this here), encouraging women facing abuse on Twitter to tag them in tweets. They would then swoop in to provide abusers with some hilarious and much-needed advice on how to ‘reform’ their behaviour.

The problem is that while such community-led initiatives to alert allies to abuse keep sprouting up across the interwebs, they never seem to last for very long. The reasons for this might range from financial strain (funding such long-term and full-time operations is never easy) to the fact that, with so many ‘helpful’ hashtags and accounts to choose from, it can be confusing for women to figure out where to go.

What’s more, once you tag a tweet or post asking for help, you’re not in control of what sort of assistance comes your way. #MisogynyAlert, for example, kind of died because the hashtag itself had started to attract trolls, thus undermining its usefulness.

Allies are almost equally unpredictable: they, too, might be too polite, too aggressive, too many, too few. And sometimes, what might have started out as a call for a little support gets way out of hand. Like here, and here.

And yet, sometimes hashtags just work fabulously – as in the case of initiatives looking to spread some love to women in power, particularly those who’ve been regular targets of abuse. #AbbottAppreciation is a perfect example. Thousands of women and marginalised folks in the UK tweeted their admiration for the frequently-targeted Dianne Abbott – the first black woman to hold a seat in British Parliament – while she was on sick leave in 2017. The trending hashtag, made popular by black British women, felt like light at the end of a long, murky (read: racists and sexist) tunnel in British politics. Diane was thrilled to see her supporters rally around her:

Touched by all the messages of support. Still standing! Will rejoin the fray soon. Vote Labour!

At home, the hashtags #DalitWomenFight and #DalitWomenSpeakOut have remained some of the most inspiring spaces on Twitter and Instagram, allowing for Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi women to organise in the fight against sexual violence and caste supremacy online and offline. Both hashtags represent a thriving community, and are repositories of documentation of resistance, in India and around the world .

Takeaway

Community-run hashtags alerting others to abuse can be useful if you’re in distress: even though you can’t control the nature of the support you receive, spaces created by the likes of #DalitWomenFight and #AbbottAppreciation prove that there is power in the community hashtag.

‘How do you fix a broken system that isn’t yours to repair?’

Welcome to mutual aid technologies. Taking community accountability a step forward, the rise of mutual aid technologies has been an important way to hold users accountable, especially when platforms refuse to step in.

For Twitter, third-party apps like Twitter Block Chain and BlockTogether allow you to block whole sets of people you never want to hear from. Through these apps, you can create a list of abusive Twitter handles to block, which saves you the time and effort it takes to individually visit each abuser’s Twitter profile to block them.

What’s more, you can share your list with friends and subscribe to theirs, which means that women who are getting harassed by similar sets of people can build on each other’s lists of handles to stay away from.

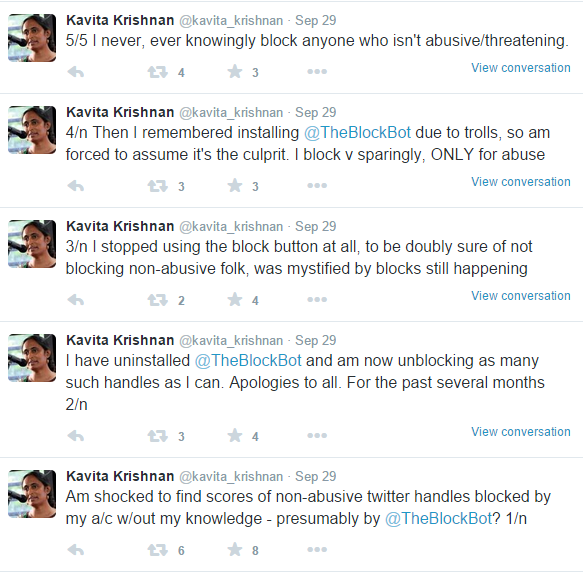

One drawback to this is that when the owner of a block list adds in more handles, you’ll automatically block these new additions too. And because you won’t be notified of the changes, you’ll only be able to unblock someone by specially visiting their profile. Which you might never get round to doing in the first place when you don’t know who has been added to the list, when, or why!

Which is exactly what happened to Kavita.

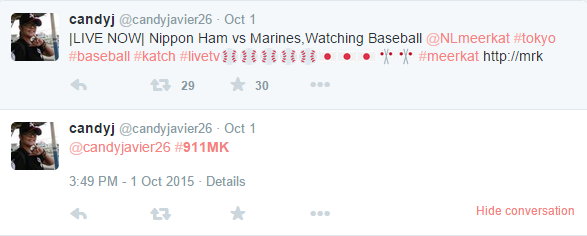

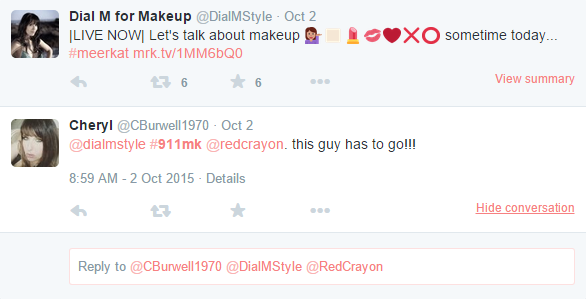

What happens when third-party blocking tools don’t exist? Well, digital strategist Suzanne Nguyen devised a makeshift solution during her time at Meerkat. This free app, which has since closed down, allowed you to livestream your Twitter account – and like with the rest of Twitter, this also meant that your Meerkat livestream could be full of abusive dudes.

By using the hashtag #911MK alongside the abuser’s username, a public watchlist would be aggregated by users that alerted Meerkat to abuse. This scrollable list made it easier for Team Meerkat to identify and deal with hashtagged abusers, often by requesting Twitter to suspend their accounts.

Platforms themselves have slowly started to learn from these kinds of

third-party programmes. As of June 2015, Twitter allows you to export

and import block lists straight from your account. And in 2017,

Instagram followed in the footsteps of apps like the now-defunct Spotless,

which automatically deleted Instagram comments you didn’t want to see

by creating a filter alert for certain words or slurs.

So now, if you get a lot of bitch-related insults on Instagram, you can create a filter for the word ‘bitch’ using the app’s own ‘Comment Control’ feature, which can delete all the comments on your pictures with that word (which might unfortunately also mean that your friends will have to stay away from quoting Queen Latifah’s epic feminist hip-hop anthem U.N.I.T.Y. on your selfies, because ‘Who you callin’ a bitch?’).

Takeaway

Mutual aid technologies can be effective ways to avoid abuse, alert platforms, and support each other – provided you are aware of the limitations of each technology and have figured out which one works best for you regardless.

Mutual aid technologies don’t just involve mass blocking and deletion programmes. They can also be about digitally creating ways for Internet users to more easily come together as a collective – not only to combat online abuse, but also to support women in crisis.

In early 2015, Hollaback!, a non-profit working towards reducing harassment in public spaces, raised money on Kickstarter to launch Heartmob. The platform describes itself as one that ‘provides real time support to individuals experiencing online harassment and empowers bystanders to act’.

It works like this: you report harassment to Heartmob. If you choose to make your report public, you pick ways in which volunteers can help you out, either through support, taking action, or intervening. Which is a great way for those targeted by harassment to direct the nature of the support they receive, as well as for a range of people – including women who have themselves been in similar situations earlier – to volunteer and be part of the solution.

Also in 2015, survivors of #GamerGate violence Zoe Quinn and Alex Lifschitz launched Crash Override Network, an ‘anti-online hate task force, staffed by former targets, providing resources, outreach, and support to combat mob hatred and harassment’.

The Crash Override Network hotline provided victims of abuse with

post-crisis counselling sessions, help in seeking shelters, access to

experts in information security, public relations, threat monitoring,

and much more.

While the Network was similar to Heartmob in that it provided a customised plan for each survivor, the plans of Crash Override didn’t just seek to provide instant aid to cope with a specific incident. They looked at comprehensive long-term support in the event of escalations and serious security risks, and in situations that require law enforcement intervention. Especially useful for when things really get too much.

Although its public tools and resources are still available, sadly the requests for assistance with online abuse outpaced the initiative’s resources to such an extent that it had to close down its private helpline in 2016.

Closer to home, however, and still very much up and running, is the toll-free service operated by the Digital Rights Foundation (DRF), a women-led advocacy group in Pakistan.

Well-versed in South Asia’s social, cultural, and religious complexities, DRF understands that the fear of self-exposure is often why targets of online abuse, in Pakistan and beyond, don't open up about their traumatic experiences. So, within their dedicated Helpline rooms, DRF’s trained staff operate with the strictest confidentiality while working to provide psychological, technical, and legal support to callers in cases of online abuse and threats to digital security.

DRF’s Helpline facility is a truly incredible initiative from our sisters in Pakistan – prioritising privacy, and action, in their defence of the rights of women and minorities online.

Takeaway

Mutual aid technologies include more than just blocking tools. They can also involve organisations of different sizes, based in diverse parts of the globe, looking to provide effective support to targets of online abuse in their region – in ways that can be tailored to suit individual needs.

With tons of community-led initiatives to counter abuse underway, here’s one that tries to tackle abuse before it begins.

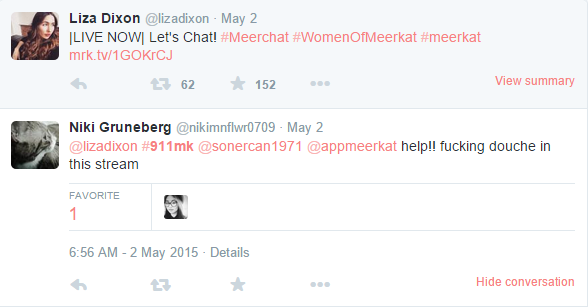

You might have noticed the little blue box at the bottom of our home page, showing two hands, with index fingers and thumbs touching, and the words ‘Respect Zone.org’ underneath.

The Respect Zone calls itself ‘a new, positive tool to counter cyberbullying’, and here’s how it works:

By displaying The Respect Zone label on your website (like we’ve done), blog, profile, or handle, you agree to respect others by only creating, publishing, or allowing content that ‘recognises the fundamental rights and liberties of other people, whether in online or offline contexts’. You also agree to remove content that violates these rights and to disassociate yourself from such content. Which all sounds good to us.

Takeaway

The flipside of abuse is respect, and making a public statement about respectful content is a good way to let people know the kind of community you want to be a part of.

Companies could take a leaf out of that book as well – and some have done just that. While the world of gaming has been one of the big hotspots for gender abuse online, some gaming platforms have developed rather wonderful anti-harassment initiatives that rely on the support of their communities. And in their attempts to understand and respond to online abuse, they’re hopefully paving the way for other platforms to do the same.

In a Wired article, Laura Hudson explains some of these efforts. She says,

If you think most online abuse is hurled by a small group of maladapted trolls, you’re wrong.

In fact, nearly 90% of abuse comes from players who seem to, for the

most part, be inoffensive or even positive. These ‘regular’ users lash

out occasionally in isolated incidents, but as Laura explains, ‘their

outbursts often snowballed through the community’.

In response, Riot Games launched a disciplinary system called The Tribunal, in which a jury of fellow players voted on bad behaviour. And it didn’t only seek to discipline, but also to rehabilitate. They received tons of apologies from players, including requests to be placed in a Restricted Chat Mode.

Since The Tribunal’s launch in May 2011, over 280,000 censured gamers

have been elevated to good standing. The only problem is that The

Tribunal has been under maintenance for several years now, with no

indication that it’ll be enabled again any time soon. Hmm.

In a similar vein, Microsoft has developed a community-powered rating system for players on its new Xbox One console. Combining feedback from users with a variety of their own metrics, players get rated green (‘good player’), yellow (‘needs improvement’), and red (‘avoid me’).

Takeaway

By empowering online communities to create better spaces, platforms, too, can curb harassment and cultivate a culture of respect in a meaningful way (hint hint, Facebook, Twitter, and co.).

When there are no such systems in place, a massive self-organised response can be helpful.

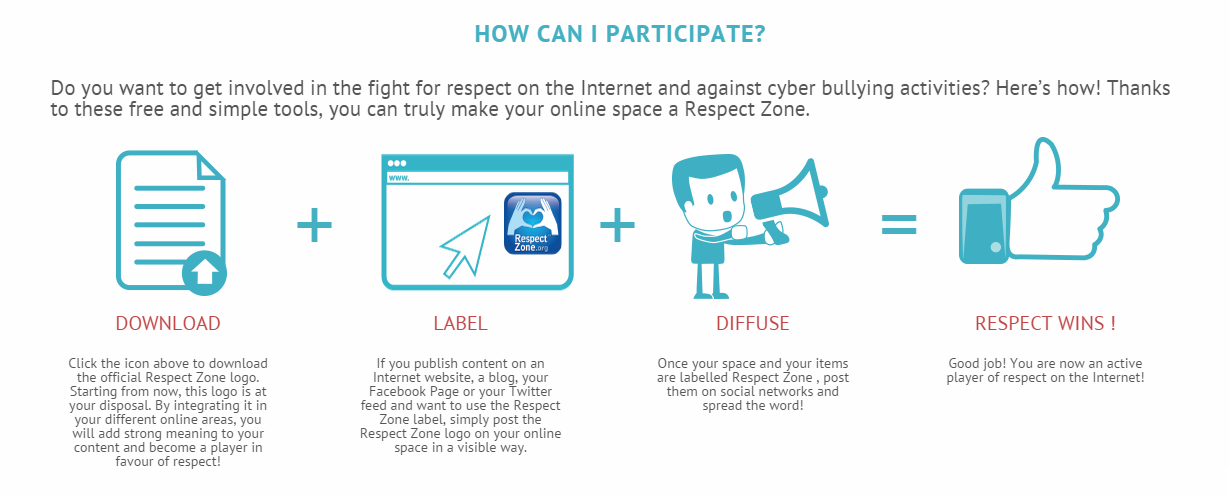

In October 2015, technology activists planned a global Twitter chat to discuss the impacts of online violence against women. The hashtag for the conversation was #takebackthetech.

But on the day of the chat, #takebackthetech was swarmed by #GamerGate supporters.

If you’re not familiar with #GamerGate, here’s a handy article. Long story short, #GamerGate went down in 2014 when several women in the gaming industry were attacked by men who claimed to be defending ‘ethics in gaming journalism’. In reality, #GamerGate supporters stalked, harassed, and abused a lot of women, and continue to perpetuate similar hatred against women even today.

Aside from arguments like the infallible ‘men get harassed too’,

the comparison of feminism to the Holocaust,

and some really bizarre understandings of the world,

they also started attacking individual organisers and activists. And with hundreds of aggressive tweets, they tried to make it really tough for women to have a serious conversation about violence and abuse online.

Well, they tried.

But in an overwhelming and coordinated effort involving women and allies from across the world, the hashtag was – at least somewhat – reclaimed.

Boom.

And what’s more, the very presence of #GamerGate violence on a hashtag designed to talk about online violence only served to prove how much the conversation needed to happen. And thanks to this fabulous community effort, it took place in full glory.

Takeaway

When communities rally together in the face of mass abuse, their rallying is in and of itself a victory.