Making Abuse Public

Facing online abuse can be an isolating experience. Most of the time it’s just you, your keyboard, and a lot of awfulness coming your way. It can be scary, and can make you feel really alone.

One way to deal with this is to make the abuse public. On highly public platforms like Twitter, this might entail retweeting or quoting an abusive tweet. On semi-private platforms like Facebook, it might involve screenshotting a hateful message or comment and publishing it on your profile page. Or you might blog about your experience, sharing examples and pictures of abuse.

These are all ways to make the abuse known to a larger group of people. They can also be used to shame abusers.

‘I retweet the abuse because people should know that kind of misogyny exists. They [misogynists] need to be called out’

-- Sumona, interviewed for Don’t Let it Stand

What’s more, making abuse public can be a way for women to feel supported by an online community, and may even occasionally lead to action being taken against the abuser(s).

***The below contains illustrated examples of online abuse that readers might find distressing***

On platforms like Twitter, the majority of abuse is public to begin

with. Retweeting that abuse (often with some added commentary – wry, outraged or funny, depending on the occasion and your mood) is a way to alert your followers and the wider Twitter community to what’s going on.

Activist Kavita Krishnan receives heaps of abuse, which she often collates and shares with her followers. Oh, and she adds in a few strong words.

This doesn’t go unnoticed by her community, who congratulate her for staying strong.

Similarly, Twitter user @Vidyut has daily mentions filled with hate, and doesn’t shy away from making them public.

Oftentimes, her followers step in to help.

Takeaway

Making public abuse even more public can be an effective way to shame harassers for their behaviour and for women to get support from online communities.

Ah, the world of unsolicited dick pics. A.k.a. sexual harassment. A.k.a. a pretty horrific and traumatising picture to find in your inbox. When ScoopWhoop editor Sonali Mushahary received a photo of a penis in a Facebook message, she wrote an article sharing a screenshot of her inbox, providing readers with the option to view the picture itself.

Obviously, this poor guy feels lonely and craves…human attention. He wants friends who will love and support him through the ups and downs of life. So, I've decided I'm going to introduce everyone to this needy dude and make him famous, so that he can make friends and get a life.

She goes on to share a picture of him and the personal details on his Facebook profile.

The results? Well, the abuser didn’t show his penis – sorry, face – again, and hopefully other potential dick-pic-senders who read her piece felt at least a tiny bit deterred from harassing women.

Takeaway

Making abuse public on your own terms can shift the power away from abusers and put control over the situation in your hands.

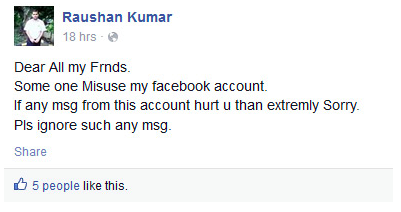

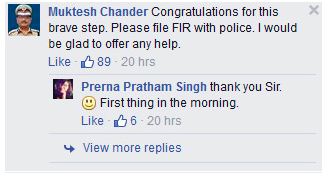

In May 2015, Prerna Singh received a sexually harassing message in her Facebook inbox from a man she’d never met. When she took a screenshot of the abuse and made it public, she received a ton of support online, including from the Delhi Police. In turn, her harasser posted an apology status saying that his account had been hacked (yeah right).

In a bizarre turn of events, Facebook deleted her post, citing that it violated their community standards pertaining to ‘nudity content’.

The only thing that came close to nudity was the harasser’s use of the Hindi equivalent of ‘cunt’, which is widely considered to be vulgar and often used as a swear word.

Women

from different parts of the world have been trying to get Facebook to

recognise abuse that happens in regional languages – with little

success so far. But mysteriously, Facebook had no trouble reading

this

particular Hindi word when Prerna re-posted it. Or maybe none of this

is very mysterious in light of Facebook’s anti-women policies.

In any case, Prerna Singh wasn’t going to let it stand, so she released this kickass video in collaboration with The Quint, explaining what went down and why girls and women should not sit back and ignore messages from creeps.

Oh, and this might shed some light on why Prerna’s tweet was deleted.

In July 2015, Kavithaa Ravindran, a fitness trainer from Bangalore, posted a screenshot of lewd messages from a stranger.

Facebook deleted her posts, explaining that, ‘Sharing private conversations and naming and shaming, as per our standards, violates our bullying policies.’ Go figure.

But naming and shaming her abuser still kinda worked. Kavithaa was flooded with messages of support, and three days later, her harasser deactivated his profile.

Takeaway

Many people are appalled by the kind of abuse taking place online, and will support women who make that abuse public (#ProTip: If you receive abuse on Facebook, try (also) sharing it on other social media platforms so that Facebook’s ‘Community Standards’ don’t get in the way).

Making abuse public rests on the belief that people will support you. But this is contingent on who your online communities, friends and followers are, and sometimes also on how well-known your online presence is.

If you have a big account, your followers tend to take care of you

-- Sharada, interviewed for Don’t Let it Stand

If I am retweeting abuse and nobody responds, then I feel really bad because I am retweeting for a reason

-- Vishakha, interviewed for Don’t Let it Stand

You may also be aware of contradictory dynamics amongst your followers or friends online.

I don’t always retweet the abuse because I am followed equally by people who hate me and by people who like me. The problem of putting it out in the open is that I won’t just get support. It will spread more than I want to. There is no point. It will increase the problem.

-- Nidhi, interviewed for Don’t Let it Stand

And in some cases, making abuse public can unfortunately backfire. In early 2015, San Francisco based developer Adria Richards called out two guys for sexism at a tech conference, which led to one of them being fired.

But after he wrote a post about it online, she received a ton of hate mail, death threats, and was eventually let go from her own job. The consequences of things going viral are often difficult to predict, and though this is an extreme case, it’s always possible that things may not go the way you plan.

Here’s a similar story closer to home.

Jasleen Kaur called out a guy who decided to serenade her with some colourful language at a traffic signal. She took a picture of him (which he arrogantly posed for) and posted it on Facebook.

She

received an enormous amount of support and eventually the

perpetrator, Sarvjeet Singh, was arrested.

Jasleen also received a Rs. 5000 cash award by the Delhi police for

her bravery.

But then it dawned on Sarvjeet that he had a Facebook account too – and that’s when things started going downhill for Jasleen. Sarvjeet wrote a post, sharing ‘his side of the story’, a.k.a. how he was wrongly accused. According to him, it was just a small tussle over a red light, and though no abuses were hurled, Jasleen had decided to take a picture of him anyway. He did generously acknowledge that ‘women are often harassed, but that does not mean an issue should be made out of something like this.’

Soon

the tables turned, and Jasleen started being criticised

and attacked for ‘just wanting five minutes of fame’. Also, like

all things in India that have nothing to do with politics, Jasleen’s

harassment claim was positioned

by haters as a stunt of the Aam Aadmi Party which Jasleen supports.

She was further discredited on that basis.

Jasleen

took to Facebook again to debunk

all the rumours surrounding the incident. Later she pointed out

how society was always ready to side with the guy over the girl, and

that this is why so many cases of sexual harassment go unreported.

Takeaway

In an unfair but not uncommon twist of Internet fate, sometimes those who speak about abuse get positioned as abusers themselves. But hopefully for every person who discredits your claims, there will be someone who supports you too.

It’s true that one problem with sharing abuse on a very interactive platform is that you might become the target of even more abuse. Or at the very least, it might give abusers the opportunity to attack your explanation of how things went down.

Enter Storify.

Storify is a social network that lets you create stories using content from Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms. And increasingly, women are finding it to be a super useful way to archive stories of abuse. While it’s true that abusers can still comment on your storify, like comments on a blog, they’ll be all the way at the bottom of the page. Your story will remain intact and uninterrupted: just the way you think it should be told.

In fact, Storify has become a pretty popular platform for archiving abusive behaviour by GamerGate supporters.

(At this stage if you’re like, ‘GamerGate who?’, do read this handy article. Long story short, GamerGate went down in 2014 when several women in the gaming industry were attacked by men who claimed to be defending ‘ethics in gaming journalism’. In reality, GamerGate supporters stalked, harassed and abused a lot of women, and continue to perpetuate similar hatred against women today.)

Here’s @effNOVideGames’ storify on how GamerGate has always been a spin.

A

storify by Catherine Cross on the ethical (or not so ethical)

landscape of GamerGate

And

then there’s this super informative one by @a_man_in_black about

GamerGate’s misogynistic origins

So

if every time you share abuse you’ve got a bunch of people telling

you to be quiet – or trying to disprove you – take your story to

another platform where it can be told on your terms, in full detail,

with no interruptions.

(You can of course also use Storify to document your own community’s fightback against abuse, as activists from Take Back The Tech did when they got viciously attacked on Twitter by GamerGate supporters – read more about that here).

Takeaway

Storify is a useful platform to archive abuse, because it puts you in the driving seat when it comes to how your story is told, while still making it possible for you to share that story with the world.

In February 2015, Sunitha Krishnan launched #shametherapist in response to viral rape videos that were doing the rounds on Whatsapp. It’s unfortunately increasingly common for rapists to record an assault and use the threat of the video being made public as a means to silence survivors. When Sunitha was anonymously sent nine of these videos, she edited them to blur out the bodies and faces of the victims and released them online on YouTube, Facebook and Twitter.

This effort to mass-shame abusers online spread far and wide across social media and TV. While not everyone felt it was ethical to have released the videos without the consent of the survivors, a month and a half later (because unbelievably that’s the speed law enforcement works at), the CBI made their first arrest. In an interview with Women in the World Sunitha says:

I don’t believe in vendetta, but I think it’s time to use their own weapon on them. Technology can help rape survivors to tell their truth too.

Her campaign received a ton of support.

Between

February and April 2015, over 90 rape survivors sent Sunitha links to

similar videos, hoping that it would lead to a CBI investigation of

their cases, too. Sunitha pointed out that this wasn’t a long-term

solution, and has proposed a national agency with the jurisdiction to

act on such offences. She explains:

The problem is that cyber cell does not take suo motu (on its own) notice of the videos. There should be a complainant. But sadly nobody wants to become a complainant as revealing one’s identity is risky. I urge the Supreme Court to put in place a public-friendly system where public can report such videos anonymously.

-- Sunitha, quoted inThe Daily Mail

In August 2015, the Supreme Court asked the Ministry of Home Affairs to respond to her proposal by August 28. But on that date, the Supreme Court then instead asked the Information Technology Ministry to come up with a temporary solution to block the videos. It’s unclear what happened to the original request to the Ministry of Home Affairs, and there have been no developments reported since.

The most significant consequence of her campaign has been the creation of a national online portal by the Ministry of Home Affairs, which has enabled reporting of cyber crimes involving child pornography and rape content. Complaints can be filed by individuals or by NGOs, and there is also an option to do this under the cloak of anonymity.This is a huge step forward in legal spheres for cyber security in India, a success that is owed in no small part to the #shametherapist campaign.

Takeaway

Sharing abuse can be an effective tool leading to legal action. If you are sharing someone else’s experience of violence, it is a good idea to first check how they feel about it, though.