Taking on the tech companies

One of the big problems with many online spaces—and in particular

with social networks—is that we don’t own them. We’re essentially

playing in someone else’s playground, and the owners care a lot more

about profiting from our selfies than reprimanding schoolyard bullies.

Patreon shutting out adult content creators from their site. Instagram's guidelines being antsy around female nipples. Twitter suspending the account @KunanPoshpora, which documented crimes committed against Kashmiri women.

The policies and reporting mechanisms of most social media platforms rarely end up benefitting their most vulnerable users.This includes trans women, bahujans, sex workers, and essentially a long list of everyone who isn’t an upper caste, straight, able bodied, cis-gender man.

The good news, though, is that we also make big tech companies what they are. Facebook is Facebook because we’re all on it. MySpace is no longer what it used to be because we all left it.

Taking on tech companies can involve community campaigns, individual fightbacks or even lawsuits.

Even though we’re up against giants, there’s still a certain amount of power in our keyboards. So let’s use it.

***The below contains illustrated examples of online abuse that readers might find distressing***

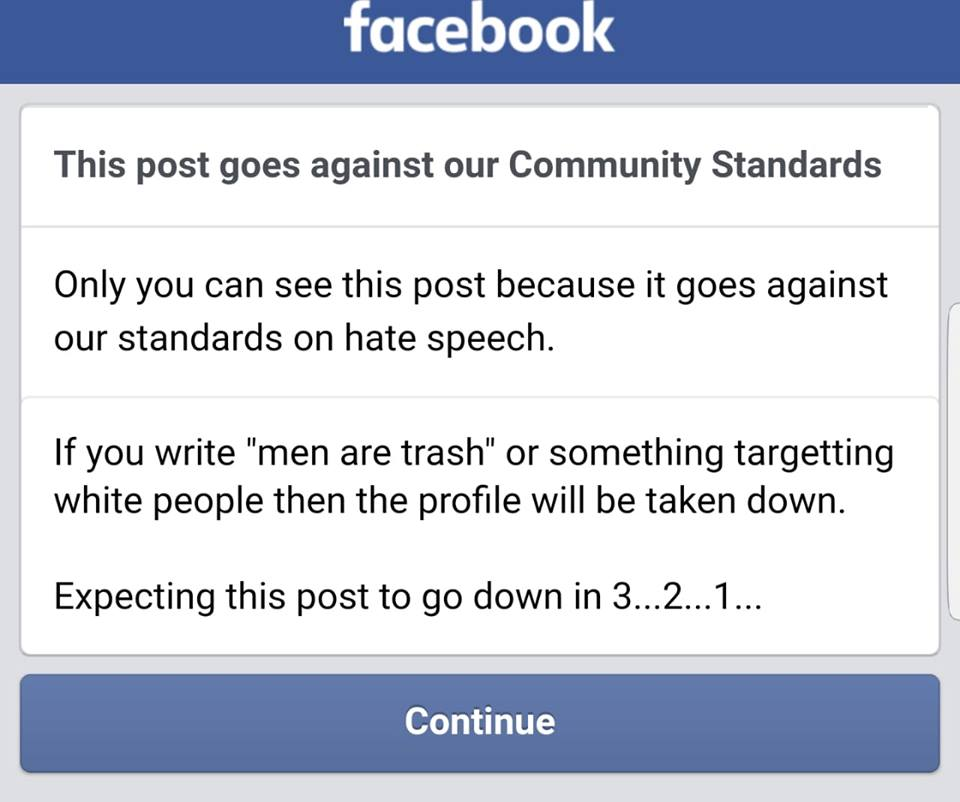

Ah, Facebook. The platform that seeks to 'encourage expression and create a safe environment' but won't ban a popular page that is deemed a male-supremacy extremist group by the Southern Poverty Law Center while freely labelling satirical comments about men being 'trash' as having violated their community standards.

So it’s not surprising that Facebook’s inability to recognise gender-based hate has emerged as a huge problem.

In 2015, Preetha Nair spoke out on the social media platform against the politics of ex-President Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam. The resulting abuse was vicious, vile, and overwhelming.

Calling her everything from a ‘bitch’ to a ‘prostitute’, her abusers set out to create a fake Facebook profile in her name. This fake page, featured in the screenshot below, even contained images of her children, along with hateful and sexually explicit content.

[Translation: Page name: 'Preetha G Nair - Facebook Firecracker (Prostitute), Shikhandi (Transphobic slur), and Female Thug'. Post: 'Does Preetha have the courage to come here and say who the father of her child is?' The bottom two comments imply that the abuse is going overboard.]

Despite several users reporting the profile to not only Facebook but also to the Kerala Cyber Cell, a month later it was still active.

But how could Facebook – with all its claims of progress – have allowed such a sustained cyber attack?

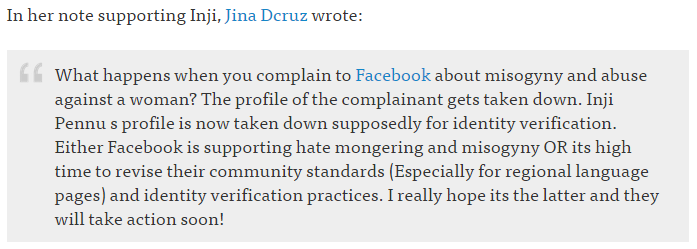

Inji Pennu, a writer for Global Voices, noted that the problem was distinctly one of language.

Any person who knows how to read in the Malayalam language can understand that Preetha G Nair is being subjected to massive online abuse… This poses a question: who is monitoring Indian Facebook pages?

Of course, this is also when Inji got dragged into things. Preetha’s harassers flocked to Inji’s Facebook profile, with one user threatening to choke her at a beach in Miami (where Inji lives). All in Malayalam regional slang, of course. And, so, seemingly undetectable on Facebook.

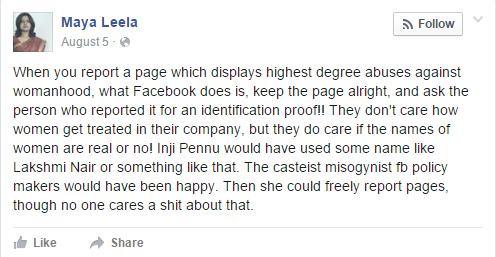

Preetha worked to report them, but then Facebook suspended Inji’s account instead, alleging she was using a ‘fake name’ (‘cause, you know, all those fake-sounding desi names). The crappy cherry on a crappier cake. On the other hand, the accounts of the abusers were thriving, despite being in total violation of Facebook’s ‘Bullying and Harassment’ policies.

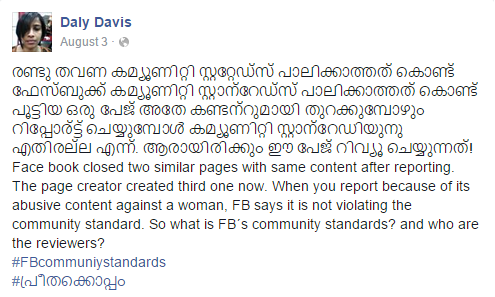

Fed up with Facebook’s lackadaisical response towards gender abuse - particularly in regional Indian languages – a group of women created a page called ‘Against cyberattacks on women’, which targeted Facebook’s ‘lousy policies’ on the matter. The page garnered an overwhelming response within hours after it was created.

Meanwhile, the hashtags #preethaismyfriend and #പ്രീതക്കൊപ്പംgathered support across Facebook, and many women and allies offered support in both English and Malayalam to Preetha and Inji.

Many posts condemned Facebook’s broken community standards

Others highlighted the website's lack of interest in dealing with the millions of users that post in Indian regional languages.

It was perhaps the first time that people in India had come down so hard on Facebook vis-à-vis its gender troubles and failures with regional Indian languages. And they used Facebook's own tools – groups, hashtags, and statuses – to do it.

This online movement did have some impact on getting Facebook to notice their issue.

Several activists, including the Internet Democracy Project, held two online meetings with Facebook’s U.S. and South Asia policy teams to discuss introducing regional language experts to assess hateful content across cultural pages. And Facebook now continues to work on translating their community standards into more languages. Which is something.

But while it looks like the company has finally, in late 2018, started to expand its capacity to take down hateful speech in Indian languages, we’re all really still waiting for Facebook to get its act together when it comes to harassment in regional languages.

Takeaway

Developing hashtags, groups, and other spaces for people to talk about a platform’s poor policies can be a way to get them to pay attention.

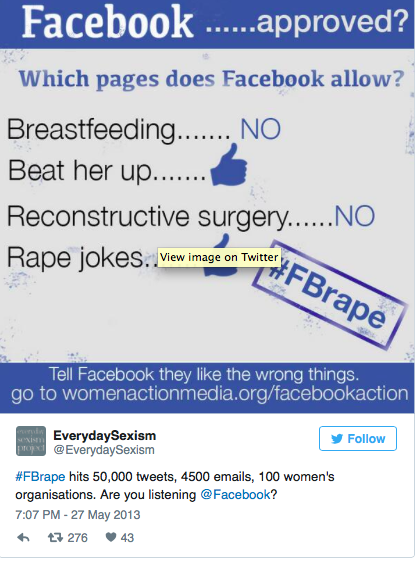

In May 2013, three feminist activists - Jaclyn Friedman, Soraya Chemaly from Women, Action & the Media, and Laura Bates from The Everyday Sexism Project - wrote an open letter to Facebook, pressuring the platform to recognise and work against the violent treatment of women online.

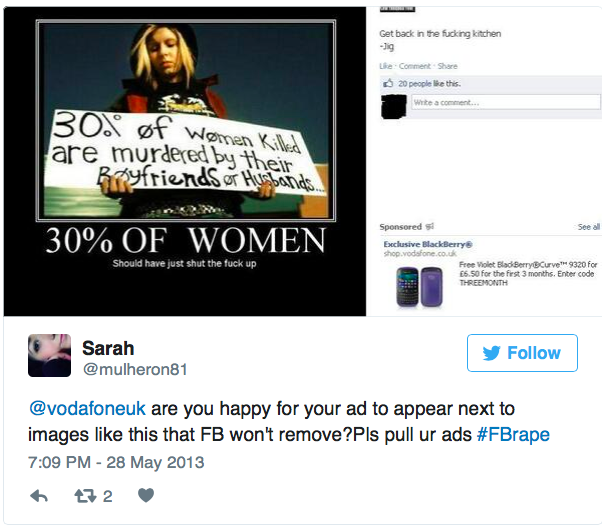

What made this letter really effective was its specific request to Facebook users worldwide.

It asked them to urge companies that advertised on Facebook to take action against online sexism, particularly if their ads tended to randomly appear right next to misogynistic content. The idea was to get these companies to withdraw their advertising (goodbye, revenue!) through public backlash until Facebook fulfilled the demands of the open letter.

Soon, the letter – and its fab strategy to mess with Facebook's

revenue and profits until they noticed – spread across social media like

wildfire.

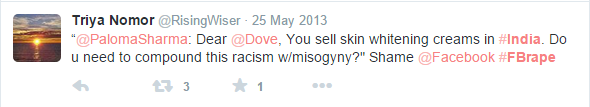

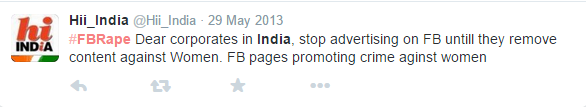

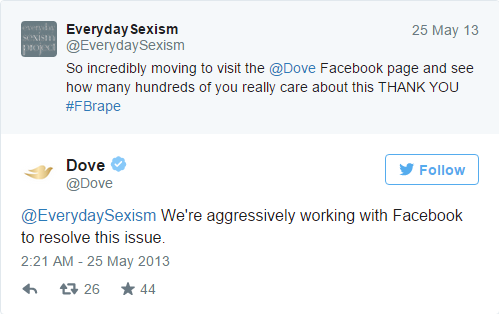

Requests to companies were sometimes organised under the hashtag #FBrape on Twitter and Facebook.

Dove was one of the first major companies to respond to the open letter.

And then Nissan UK officially expressed their support.

Fifteen other companies soon followed suit.

A month later, Facebook VP of Global Public Policy, Marne Levine, wrote in a blog post:

In recent days, it has become clear that our systems to identify and remove hate speech have failed to work as effectively as we would like, particularly around issues of gender-based hate... We need to do better - and we will.

She then listed the steps Facebook would take to revise its guidelines to make the platform a safer place for women.

Facebook appeased their advertisers, and we got a slightly better Facebook. That's what we call a win-win.

The original activists were ecstatic. Laura says:

We have been inspired and moved beyond expression by the outpouring of energy, creativity and support for this campaign from communities, companies and individuals around the world. It is a testament to the strength of public feeling behind these issues.

And from Jaclyn:

We are reaching an international tipping point in attitudes towards rape and violence against women. We hope that this effort stands as a testament to the power of collaborative action.

Takeaway

Involving tech companies' advertisers can be a very effective campaign strategy because it hits these companies where it hurts the most - their revenue.

Since there’s no dearth of problematic content and policies on Facebook, the fab ladies at Feminist Admins Support

kept out a vigilant eye for a really long time. A blog with the tagline

‘Facebook should not be a platform for rapists or violence against

women. Let’s work together to change that’, Feminists Admins Support was

an online evidence-gathering project.

Evidence of Facebook’s misogyny, racism, homophobia and double standards, that is.

Here are just a handful of the many, many posts on the blog.

When Facebook didn’t like lesbians.

The time when Facebook didn’t like indigenous people.

Aside from archiving instances of Facebook’s poor policies from across the world, the blog also provides links to protests, petitions and open letters, encouraging people to get involved in the fight against Facebook’s prejudices.

Though Feminist Admins Support seems to be no longer active today, we are grateful for everything they have done over the years!

Takeaway

Documenting evidence of a company’s poor policies in action can help build a wider case against them and feed into other campaigns.

Instagram (owned by Facebook) has had many run-ins with folks who

menstruate because they don’t seem to like the reality of human bodies.

Or at least not in their natural, visceral, and un-photoshopped form.

In May 2015, poet and photographer Rupi Kaur shot and uploaded this very realistic photo series entitled ‘Period’.

Instagram swiftly took down this ‘offending’ picture:

They cited their Community Guidelines, which is strange because they have rules against sexual acts, violence and nudity – but nothing about menstrual blood.

Rupi writes on Facebook:

thank you Instagram for providing me with the exact response my work was created to critique…i will not apologize for not feeding the ego and pride of misogynist society that will have my body in an underwear but not be okay with a small leak.

Let’s take a moment to say #BOOM.

Rupi uploaded the ‘offending’ photo along with the rest of the series

to Facebook, where surprisingly, it was allowed to remain.

Her post gained immense popularity and was shared over a thousand times.

Instagram ended up issuing an apology (yes, wow, an apology!) and reinstated the photo.

Their email to her read:

A member of our team accidentally removed something you posted on Instagram. This was a mistake and we sincerely apologise for this error. We’ve since restored the content, and you should now be able to see it.

Okay, so kind of an apology.

Rupi writes on Facebook:

we did it. you did this. your belief in the work… your movement to not quiet down has forced Instagram to place deleted photos back on my grid…imagine that. you made a giant see that it is only a giant cause you are part of it’s [sic] existence. that is the power you hold my beautiful people.

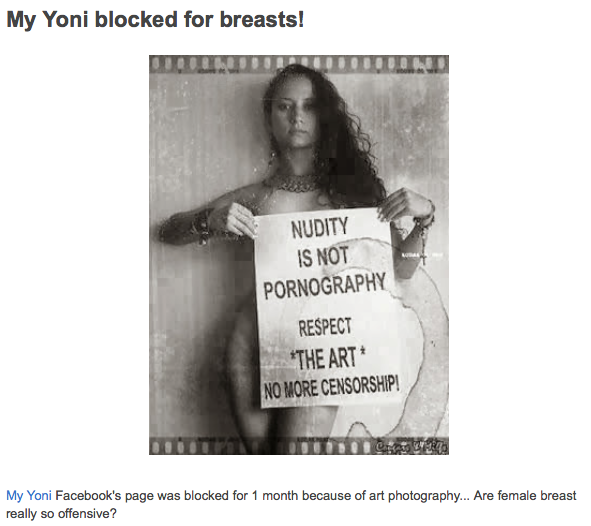

Rupi’s case was neither the first nor the last time that Instagram’s ‘nudity’ policy waged war on realistic bodies.

In January 2015, Instagram took down this photo uploaded by Australian magazine Sticks and Stones because it showed two women’s pubic hair.

Because you know, all of us are hairless, naturally Brazilian-waxed creatures. And anything else is gross.

Like this photo taken by photographer Petra Collins.

Natural? Ew.

(FYI: there are tons of pictures on Instagram where cis men have their pubes out, but that’s apparently fine.)

Instagram also went as far as to delete Sticks and Stones’ account, though after public outcry (yay for public outcry), they reinstated both account and photo.

Remember what Rupi said?

You made a giant see that it is only a giant cause you are a part of its existence.

Publicly taking on a company’s misogynist policies is a way for you

to remind a platform that they are only powerful because of you, the

users. And that you simply won’t stand for this.

Takeaway

Standing up for those who are being subjected to unfair policies and censorship are important ways to show solidarity and get companies to reverse their decisions.

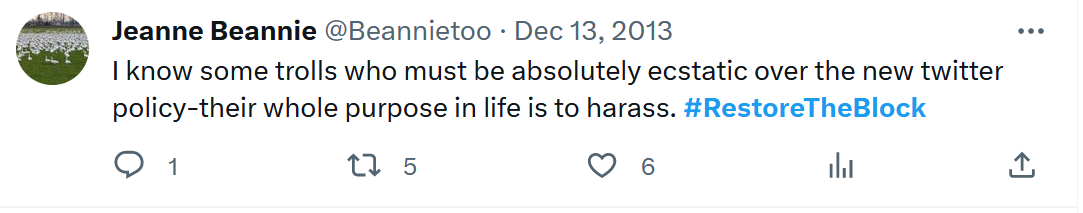

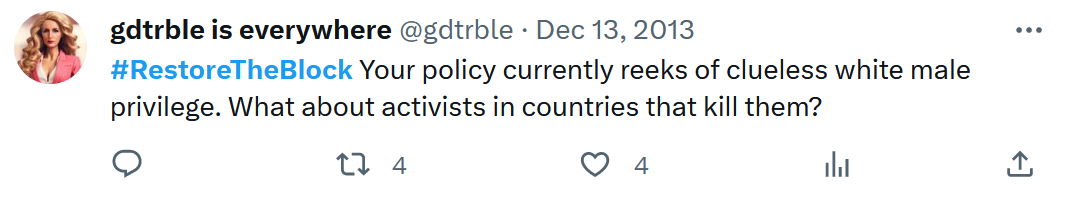

In 2013, Twitter removed the ‘block’ option because they ‘want[ed] to reinforce that content in a public sphere is viewable by the world’. Even if, you know, some portions of the world want to stalk and harass you.

For many, the ability to block users is invaluable in the face of ongoing abuse. The popularity of mutual aid technologies such as BlockTogether illustrate just how important it is to be able to cut off all contact with an abuser. The block button also prevents harassers from retweeting you, and thereby encouraging their followers to join in the abuse.

xojane called the removal of the block button ‘telling someone who’s asking for a restraining order to just wear a blindfold.’

Within an hour of the removal of the block option, over 5000 users

had taken to the hashtag #restoretheblock to express their outrage.

Several Change.org petitions were also created, the most popular of which gathered more than 1200 signatures just an hour after it was created. It reads:

Twitter is no longer a safe space. As a public person who uses the medium for my work, I am very concerned because stalkers and abusers will now be able to keep tabs on their victims, and while there was no way to prevent it 100% before, Twitter should not be in the business of making it easier to stalk someone.

In the face of this outrage, Twitter restored the block option exactly a day after they removed it, stating

We have decided to revert the change after receiving feedback from many users – we never want to introduce features at the cost of users feeling less safe.

Yay!

Takeaway

When many users actively protest a company’s policy, it can sometimes lead to positive change.

And here are some ladies who are literally taking on the tech companies – in court, that is.

In March 2015, Tina Huang filed a class action suit against her former employers at Twitter, claiming the promotional system used a bro code relying on a secretive ‘shoulder tap’ process that left many women engineers unable to reach top positions. Tina suggested that Twitter introduce a ‘transparent and non-discriminatory job posting and application process’ to help women break through Twitter’s glass ceiling.

But in 2018, this landmark gender discrimination case – involving

more than 130 other female engineers – faced a setback in court when the

women were blocked from proceeding as a group. The judge in the case

found that there was insufficient evidence of systematic discrimination.

Huang is yet to confirm her next step.

Also in March 2015, Facebook was slapped with not one, but three lawsuits from former employee Chia Hong, who was discriminated against on the basis of her gender and race. She was also sexually harassed by her boss Anil Wilson, where, among other appalling comments, she was told to ‘stay at home and take care of her children’ and asked not be part of the team because she ‘looks different and talks differently than other team members.’

She was eventually fired and replaced by a man who had fewer qualifications and less experience than her. After a mediation session later in 2015, she dropped the lawsuits - we don’t know if there has been a settlement.

Closer to home, similar fightbacks have begun. In October 2015, Shreya Ukil, a former, London-based employee of Wipro (a massive Indian IT company), sued her ex-employers for £1 million. She’s accused the firm of sexual discrimination, harassment, unequal pay, and unfair dismissal.

‘The culture within Wipro requires women to be subservient,’ she was quoted saying in The Telegraph. She was also forced to have an affair with her boss from whom she received ‘aggressive sexual advances’.

In 2016, the court agreed with Shreya: it found WIPRO guilty of unfairly dismissing her, of direct sex discrimination and of multiple instances of victimisation. Way to go, Shreya!

Takeaway

Legal battles against sexual harassment can be long and difficult, so a big kudos to women who are taking on the misogyny of tech companies!